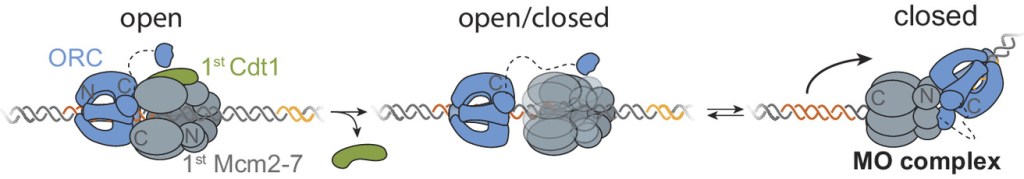

“Each time a eukaryotic cell divides (by mitosis) it must duplicate its chromosomal DNA exactly once to ensure that one full copy is passed to each resulting cell. Both under-replication or over-replication result in genome instability and disease or cell death. A key mechanism to prevent over-replication is the temporal separation of loading of the replicative DNA helicase [Mcm2-7] at origins of replication and activation of these same helicases during the cell division cycle.” Helicase loading is performed by the origin replication complex (ORC), a multi-subunit ATPase. In this study, Audra Amasino and Shalini Gupta from Steve Bell’s lab at MIT, working with Larry Friedman from the Gelles lab at Brandeis, define the mechanism by which cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of the ORC inhibits helicase loading. Loading is a multi-step process and several steps are inhibited by phosphorylation, presumably helping to ensure that loading is completely suppressed during the S phase of the cell cycle during which the helicases are activated.

Amasino A., et al. Regulation of replication origin licensing by ORC phosphorylation reveals a two-step mechanism for Mcm2-7 ring closing. PNAS, 120, e2221484120 (2023).

understood in any organism, not even in simple bacteria.

understood in any organism, not even in simple bacteria. Two separate members of the larger ADF-homology family of proteins, glia maturation factor (GMF) and cofilin, have been implicated in promoting debranching. In this paper, Gelles lab member Johnson Chung, in collaboration with Jeff and with Bruce Goode from the Brandeis Biology Dept., used multi-wavelength single molecule florescence microscopy and quantitative kinetic analysis to define the mechanisms by which these proteins promote debranching. Dr. Chung shows that “cofilin, like GMF, is an authentic debrancher independent of its filament-severing activity and that the debranching activities of the two proteins are additive. While GMF binds directly to the Arp2/3 complex, cofilin selectively accumulates on branch–junction daughter filaments in tropomyosin-decorated networks just prior to debranching events. Quantitative comparison of debranching rates with the known kinetics of cofilin–actin binding suggests that cofilin occupancy of a particular single actin site at the branch junction is sufficient to trigger debranching. In rare cases in which the order of departure could be resolved during GMF- or cofilin-induced debranching, the Arp2/3 complex left the branch junction bound to the pointed end of the daughter filament, suggesting that both GMF and cofilin can work by destabilizing the mother filament–Arp2/3 complex interface. Taken together, these observations suggest that GMF and cofilin promote debranching by distinct yet complementary mechanisms.”

Two separate members of the larger ADF-homology family of proteins, glia maturation factor (GMF) and cofilin, have been implicated in promoting debranching. In this paper, Gelles lab member Johnson Chung, in collaboration with Jeff and with Bruce Goode from the Brandeis Biology Dept., used multi-wavelength single molecule florescence microscopy and quantitative kinetic analysis to define the mechanisms by which these proteins promote debranching. Dr. Chung shows that “cofilin, like GMF, is an authentic debrancher independent of its filament-severing activity and that the debranching activities of the two proteins are additive. While GMF binds directly to the Arp2/3 complex, cofilin selectively accumulates on branch–junction daughter filaments in tropomyosin-decorated networks just prior to debranching events. Quantitative comparison of debranching rates with the known kinetics of cofilin–actin binding suggests that cofilin occupancy of a particular single actin site at the branch junction is sufficient to trigger debranching. In rare cases in which the order of departure could be resolved during GMF- or cofilin-induced debranching, the Arp2/3 complex left the branch junction bound to the pointed end of the daughter filament, suggesting that both GMF and cofilin can work by destabilizing the mother filament–Arp2/3 complex interface. Taken together, these observations suggest that GMF and cofilin promote debranching by distinct yet complementary mechanisms.” arina Herlambang, who just defended her dissertation! Karina is moving on with her Ph.D. to work as a scientist at

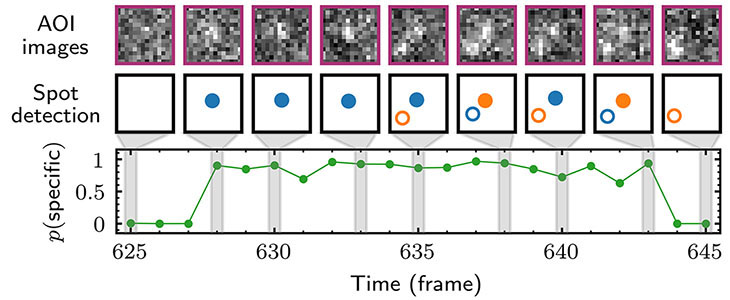

arina Herlambang, who just defended her dissertation! Karina is moving on with her Ph.D. to work as a scientist at  This work describes a holistic causal probabilistic model of CoSMoS image data formation. This model is physics-based and includes realistic shot noise in fluorescent spots, camera noise, the size and shape of spots, and the presence of both specific and nonspecific binder molecules in the images. Most importantly, instead of yielding a binary spot-/no-spot determination, the algorithm calculates the probability of a colocalization event. Unlike alternative approaches, Tapqir does not require subjective threshold settings of parameters so they can be used effectively and accurately by non-expert analysts. The program is implemented in the state-of-the-art Python-based probabilistic programming language Pyro (open-sourced by Uber AI Labs in 2017), which enables efficient use of graphics processing unit (GPU)-based hardware for rapid parallel processing of data and facilitates future modifications to the model.

This work describes a holistic causal probabilistic model of CoSMoS image data formation. This model is physics-based and includes realistic shot noise in fluorescent spots, camera noise, the size and shape of spots, and the presence of both specific and nonspecific binder molecules in the images. Most importantly, instead of yielding a binary spot-/no-spot determination, the algorithm calculates the probability of a colocalization event. Unlike alternative approaches, Tapqir does not require subjective threshold settings of parameters so they can be used effectively and accurately by non-expert analysts. The program is implemented in the state-of-the-art Python-based probabilistic programming language Pyro (open-sourced by Uber AI Labs in 2017), which enables efficient use of graphics processing unit (GPU)-based hardware for rapid parallel processing of data and facilitates future modifications to the model.

Congratulations to Dr. Deborah Tenenbaum, shown here with her two Ph.D. mentors Jeff Gelles (smiling under the mask) and

Congratulations to Dr. Deborah Tenenbaum, shown here with her two Ph.D. mentors Jeff Gelles (smiling under the mask) and  From the article: “The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the site at which secreted proteins (such as the hormone insulin) and membrane-bound proteins are folded. ATP-dependent chaperones within the ER help proteins fold. This study describes how two key ER chaperones, BiP and Grp94, work together at a molecular level. BiP binds to Grp94, which enables Grp94 to change conformation and hydrolyze ATP. In short, BiP provides a signal to switch on Grp94 conformational changes that are required to help other proteins fold. This finding helps explain how two chaperones can work together collaboratively in protein folding. Because BiP and Grp94 are members of highly conserved chaperone families, these findings may provide insight into chaperone-assisted protein folding beyond the ER.” This project was a collaboration with members of

From the article: “The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the site at which secreted proteins (such as the hormone insulin) and membrane-bound proteins are folded. ATP-dependent chaperones within the ER help proteins fold. This study describes how two key ER chaperones, BiP and Grp94, work together at a molecular level. BiP binds to Grp94, which enables Grp94 to change conformation and hydrolyze ATP. In short, BiP provides a signal to switch on Grp94 conformational changes that are required to help other proteins fold. This finding helps explain how two chaperones can work together collaboratively in protein folding. Because BiP and Grp94 are members of highly conserved chaperone families, these findings may provide insight into chaperone-assisted protein folding beyond the ER.” This project was a collaboration with members of